While he didn’t know it at the time, French surgeon Ambrose Pare was one of the first Europeans to perform a documented clinical trial. In 1537, Pare used a mixture of egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine to treat battlefield wounds. He’d run out of boiling oil, the go-to treatment at the time, earlier in the evening, and needed something to treat men returning from the front during a French expedition into Turin and Piedmont.

While he didn’t know it at the time, French surgeon Ambrose Pare was one of the first Europeans to perform a documented clinical trial. In 1537, Pare used a mixture of egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine to treat battlefield wounds. He’d run out of boiling oil, the go-to treatment at the time, earlier in the evening, and needed something to treat men returning from the front during a French expedition into Turin and Piedmont.

After spending a restless night worrying about his patients, Pare returned in the morning to find that those who’d received his special mixture had very little pain, their injuries were neither swollen or inflamed, and each had slept through the night. The same could not be said for those who received the boiling oil. They all had significant pain, and were feverish with no improvement to their wounds.

With a colorful history that dates back centuries, experimenting with different treatments for diseases has been a regular practice in medicine. Modern clinical research owes a lot to its early pioneers, and their commitment to using science to inform their work. In this post we take a quick look at the

The search for treatments that work

As long as there has been disease, there have been experiments to determine what kind of treatment works best. Some of the earliest clinical trials date back to biblical times, and the testing of treatments has coincided with the evolution of modern medicine.

In many cases, the goal of an experiment was simply to see if a treatment worked. The marker of success being that the participant either recovered or their condition deteriorated.

Practitioners anxiously looked for something to stave off what was likely the inevitable death of a patient. Combinations of foods, herbs, and chemicals, along with control of bedrest, sleep, and other environmental conditions, were tried and typically had very mixed results.

Without formal rules to direct early clinical research, treatments were often based on best guesses and assumptions from anecdotal reports. Practitioners were free to try drugs and treatments at whim. Often experiments were performed by monks within the confines of a monastery and relied on the use of herbs and other plants. For example, skullcap was a common treatment for headaches.

When a treatment proved to be successful and was put to use, its developer would often travel through Europe, selling their cure and often touting it as a panacea for every ailment. As early as the 1400s, governments took an interest in clinical trials, going so far as to offer special royal permission to sell a particular drug or tincture if it appeared promising.

Learning from the earliest clinical trials in the 1700s

The most famous and well known of these early trials is the “Treatise on Scurvy” conducted by Dr. James Lind in 1747. Working as a surgeon on a British naval ship, Lind was shocked by the number of men dying of scurvy. In response, Lind selected twelve men with similar symptoms, who were all eating the same diet, and had received care as usual for their condition.

Dr.James Lind, a Scottish Doctor who performed one of the first clinical trials.

Dividing the men into pairs, Lind gave each pair a different treatment and monitored their response. Treatments included drinking a quart of cider each day, taking drops of acid vitriol, swallowing spoonfuls of vinegar, drinking sea water, and eating two oranges and a lemon daily.

The trial also included a control group that received care as usual. The most significant improvement was seen in the pair that ate the oranges and lemons. One participant improved so quickly he returned to active duty in less than a week.

Though the results were clear, Dr. Lind didn’t want to recommend the use of oranges and lemons because they were expensive. However, citrus fruits to protect from scurvy became standard practice in the British Navy fifty years later, when lemon juice became a part of standard diets but was then replaced with lime juice because it was cheaper.

Laying the groundwork for modern clinical trials

In the 19th century another well-known element of modern clinical trials, the placebo, was identified. In 1811, Hooper’s Medical Dictionary made the first recorded reference to a placebo, describing it as “… an epithet given to any medicine more to please than benefit the patient.” The placebo effect would go on to play a critical role in modern clinical research, and is still a topic that attracts attention.

As research continued to evolve, concern over bias and false treatment claims began to gain traction. There was a clear need to establish a distinction between legitimate medical treatment informed by science and the claims made by opportunists looking to cash in.

These activities continued into the 20th century, and the scope, rigor, and complexity of clinical trials also increased. The use of statistics to develop the study design and analyze findings entered its infancy, as did emphasis on the consistent application of scientific methods to clinical research. This process included a move away from alternation towards randomized allocation in study design.

The first randomized controlled clinical trial

In 1947 the first randomized controlled trial was run by the British Medical Research Council using the antibiotic Streptomycin to treat tuberculosis. The study was designed by British statistician Austin Bradford Hill and is considered to be the defining study that launched modern clinical research.

At that time, tuberculosis was the most significant cause of death among young people in North America and Britain. The bacteria didn’t respond to penicillin, which had been discovered in 1928 by Sir Alexander Flemming, and the government and the public were anxious for a solution. Streptomycin had proved promising in animal studies, and there was an urgent need to explore its potential benefits to humans.

Streptomycin was both expensive and limited in supply, so it was decided by the research team to compare treatment with the drug to the usual standard of care – bedrest. Patients who received the drug were unaware of their participation in a trial, and consulting physicians were blinded as to the randomization allocation.

The drug proved to be useful in the treatment of tuberculosis, significantly reducing the number of deaths. After six months of admission to the clinical trial, there were four deaths among the 55 patients receiving streptomycin and 15 among the 52 that received the usual standard of care alone. Many of the components of modern trials like randomized allocation, blinding, and statistical standardization is a result of this trial.

What does this mean for the future of clinical trials?

In more recent years, the industry, along with government agencies like the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health, have tackled ethical challenges associated with clinical research. These include obtaining informed consent, representative participant enrollment, and concern over bias in research results.

Enrollment of participants is an ongoing challenge for sponsors and academic researchers alike, causing many studies to be delayed or even canceled because of low enrollment. Finding qualified participants within a study’s timeframe and budget is the most challenging part of completing a trial. This leaves the industry looking at various solutions to solve this problem.

Conducting clinical trials overseas

In response to low enrollment rates in high-income countries like the United States and Canada, sponsors have been increasingly looking to middle-to-low income countries like China and India to conduct their research. Not only does this potentially reduce labor costs directly associated with a study, but these countries have large populations to recruit from.

This approach is not without serious drawbacks, including the fact that many countries don’t have appropriate regulatory mechanisms in place. The lack of oversight exposes the corruption of many social institutions in these countries, including healthcare. As a result, there have been studies conducted abroad that have proven to be both unethical and even deadly. For example, in India, there are many reported cases of patients being enrolled in trials without their knowledge or consent.

There is also concern over trial results not being generalizable to an increasingly diverse population. It is acknowledged that environmental factors and broader social determinants of health play a role in how individuals respond to an intervention.

What this means for clinical research is that results obtained from a trial conducted abroad may not be generalizable to North American populations because of external influences like diet, environmental stress and exposure to pollution.

Using data to inform participant enrollment

Technological advancements hold significant promise for the future of clinical research. With the increasing availability of large data sets, trial sponsors and study sites can streamline participant enrollment, meet timelines and stay within budget when it’s used effectively.

Not only does data allow for easier identification of potential participants, it also enables targeted online advertising campaigns to be designed that maximize reach while being mindful of budgets.

Online advertising and other digital media strategies have replaced traditional approaches like television and direct mail, as the most effective way to reach participants.

Based on our experience, it’s crucial to ensure that participant enrollment is intentionally designed and managed at each step of the process in order to work properly. Enrollment funnels are only as good as their weakest point, so identifying where this exists early in the process can save considerable time and money down the road.

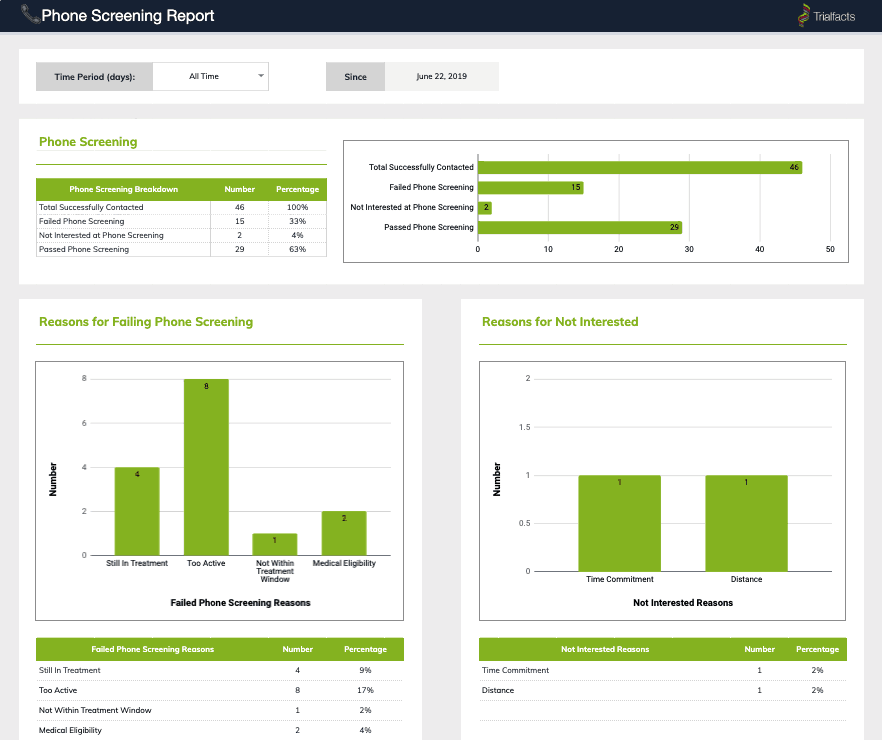

Trialfacts provides in-depth reports at every step of the recruitment process, and works with you to ensure all of your enrollment goals are met.

This means careful attention paid to inclusion and exclusion criteria and monitoring of where participants are failing screening. To do this effectively, visibility into the enrollment process is needed and often sponsors, CROs and study sites don’t start to measure and evaluate enrollment until a participant enrolls.

With Trialfacts’ Due Diligence process, we’ve increased visibility into the entire enrollment process. Using multiple data sources, the Due Diligence process identifies the number of potential participants needed at each stage of the process in order to meet enrollment targets. We’re able to bring predictability and consistency to enrollment, and help shape the future of health research.

Conclusion

With a long history that dates back over hundreds of years, clinical trials have been an integral part of medicine. Whether it’s Pare’s use of egg yolks, rose oil and turpentine to treat battle wounds or Lind’s discovery of citrus fruit’s impact on scurvy, creativity and ingenuity have been the hallmarks of success.

Central to any study’s completion is finding the right number and type of qualified participants during each stage of enrollment. Our Due Diligence process can give you the insight you need to effectively recruit for your study and proactively manage challenges before they become big issues. To find out more about how we can help, schedule a call with an enrollment specialist now.